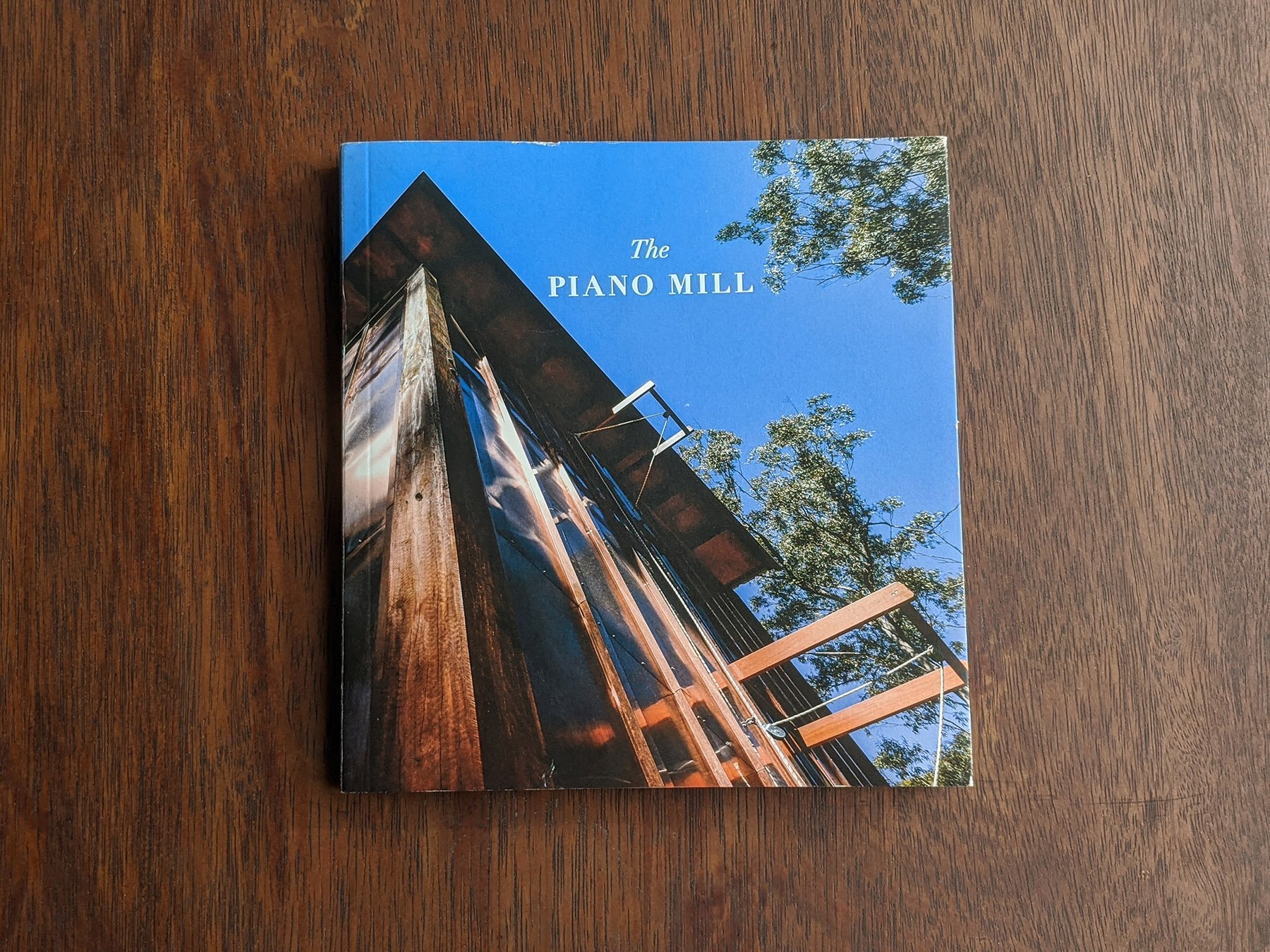

The Piano Mill

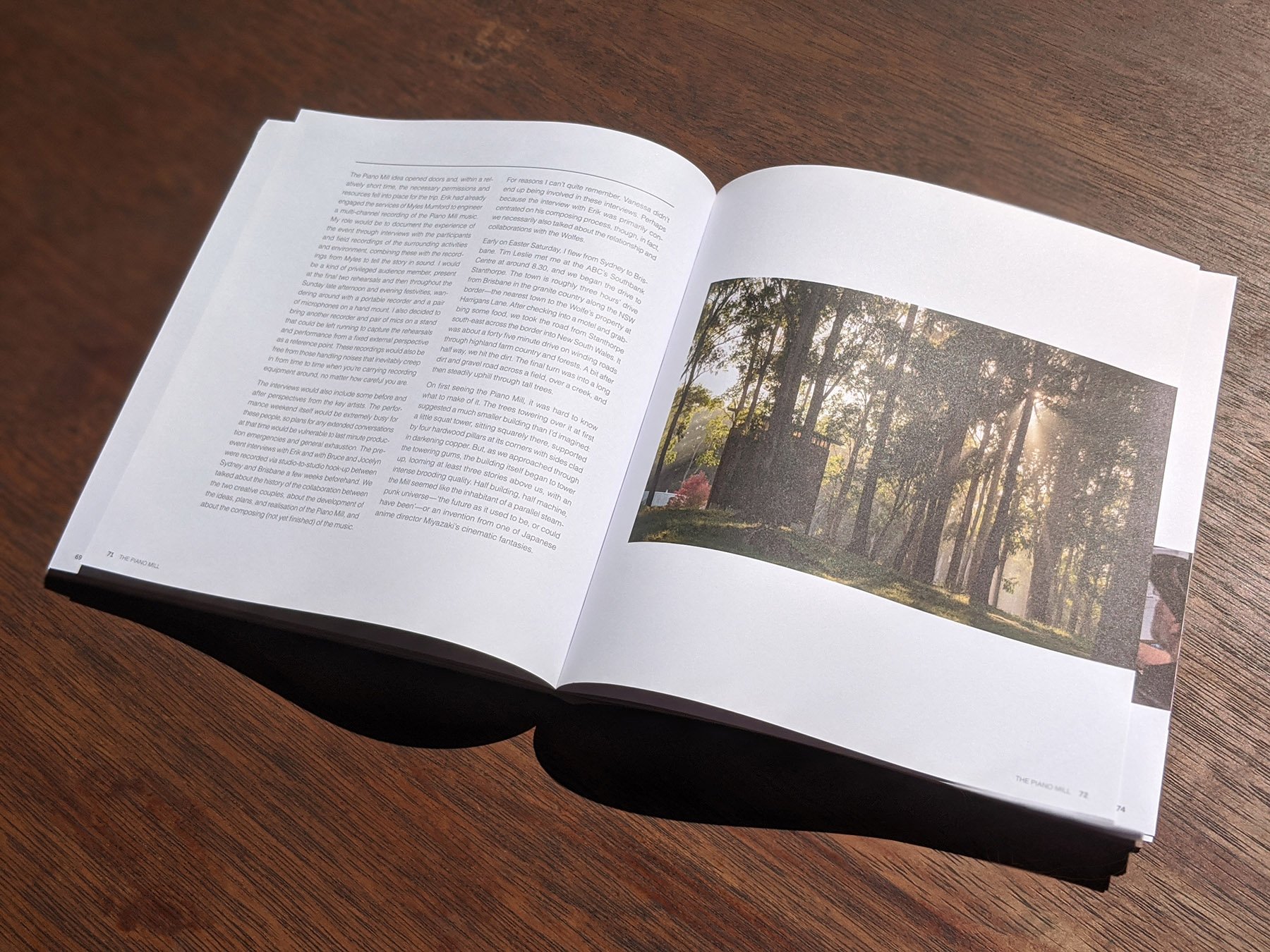

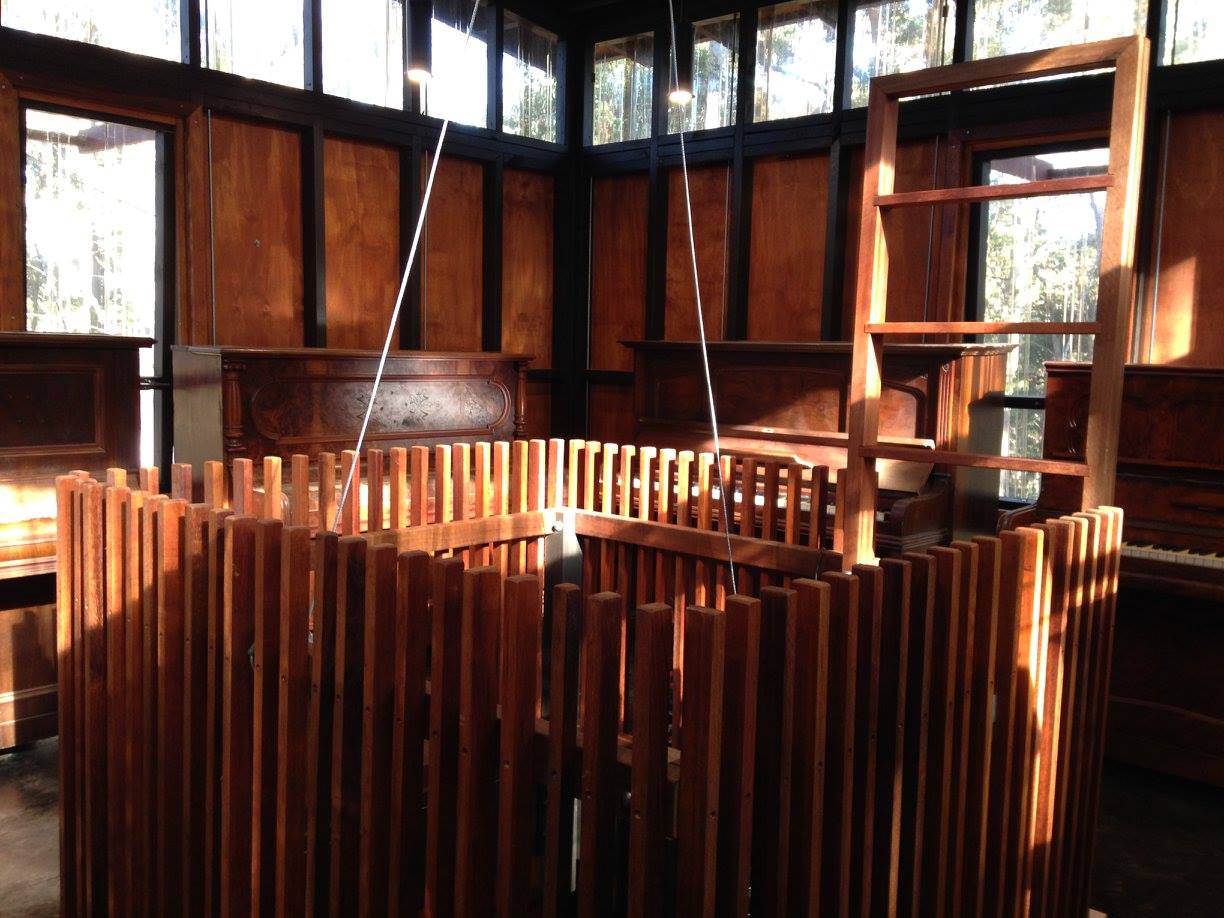

Nestled in the forest at Willson’s Downfall, near Stanthorpe, The Piano Mill is a unique architectural feature, homage to the musical history of outback Australia, and an outrageous musical instrument all in one. A square structure clad in copper, it's designed by architect Bruce Wolfe (formerly Managing Director, Conrad Gargett) and is purpose-built to house sixteen pianos — eight on the first level and eight on the mezzanine. The walls consist of large-scale louvres, which can be opened and shut to alter the Mill's acoustic.

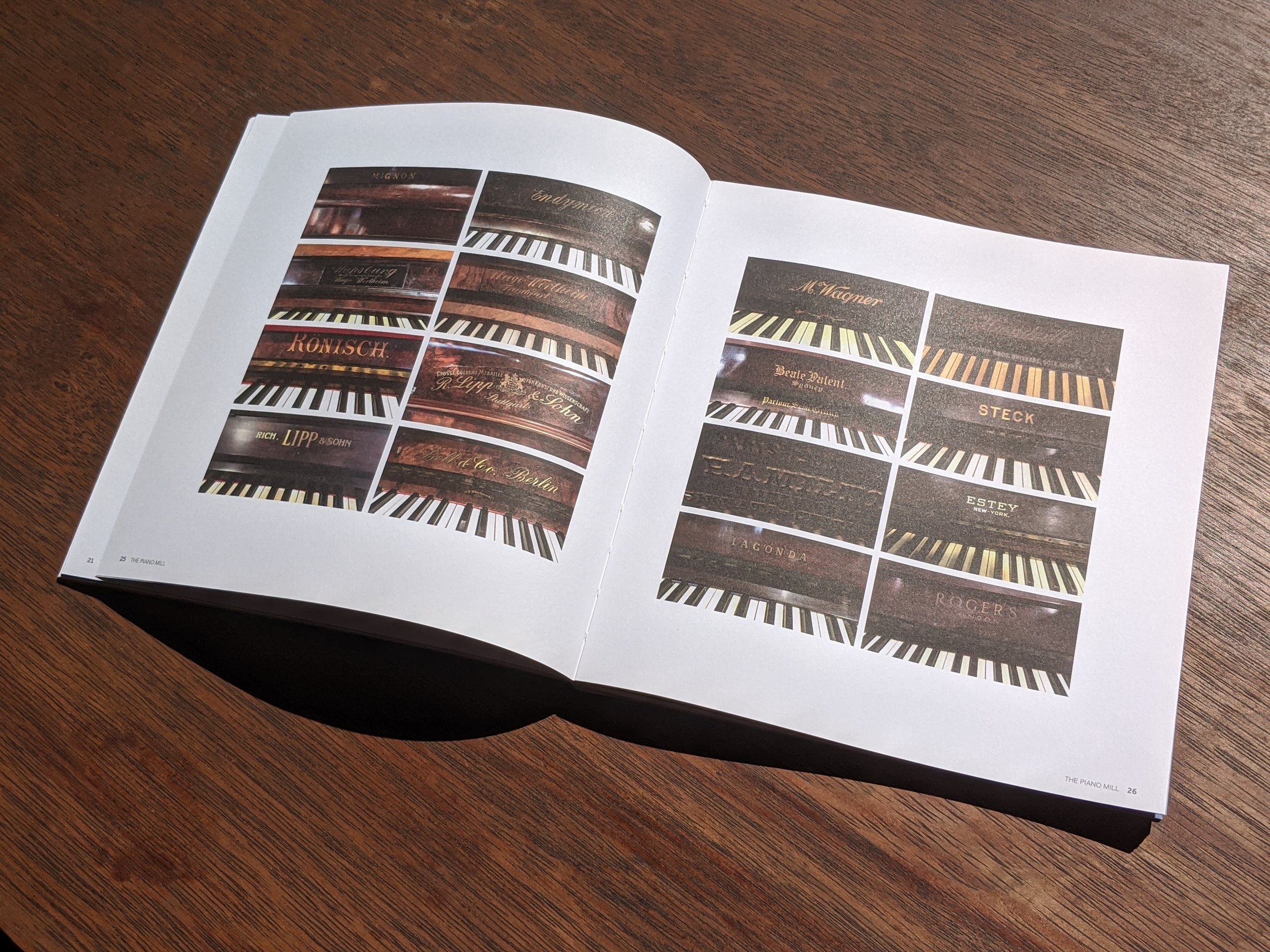

Sixteen pianos were sourced from the Brisbane, Stanthorpe, Warwick and Toowoomba areas. Many were quite serviceable, and even reasonably in tune, while a few were more dilapidated, with wonky keys and bung notes. The concept was that the pianos be kept in the original, "found" state, to evoke the weathered sound of the outback.

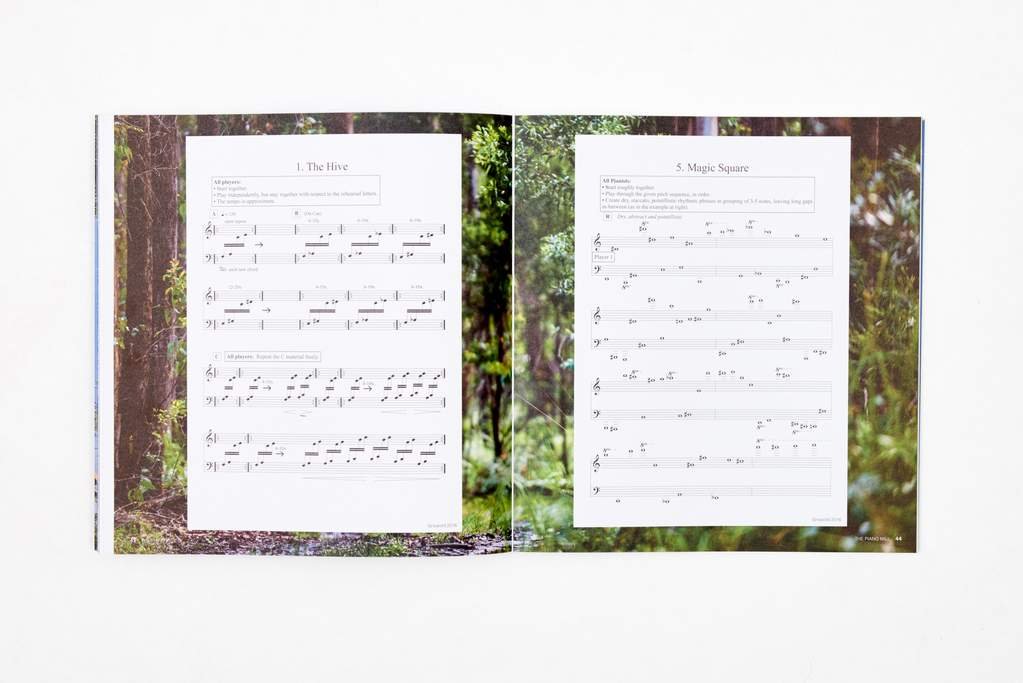

To launch The Piano Mill, composer Erik Griswold (Clocked Out) created a new concert-length work, exploring the unprecedented sound potential of this new mega-instrument. Incorporating mass sound textures, nature-inspired soundscapes, and bits of nostalgic Australiana, Erik extends his large body of piano and environmental works to new frontiers. Listen to All’s Grist that Comes to the Mill here.

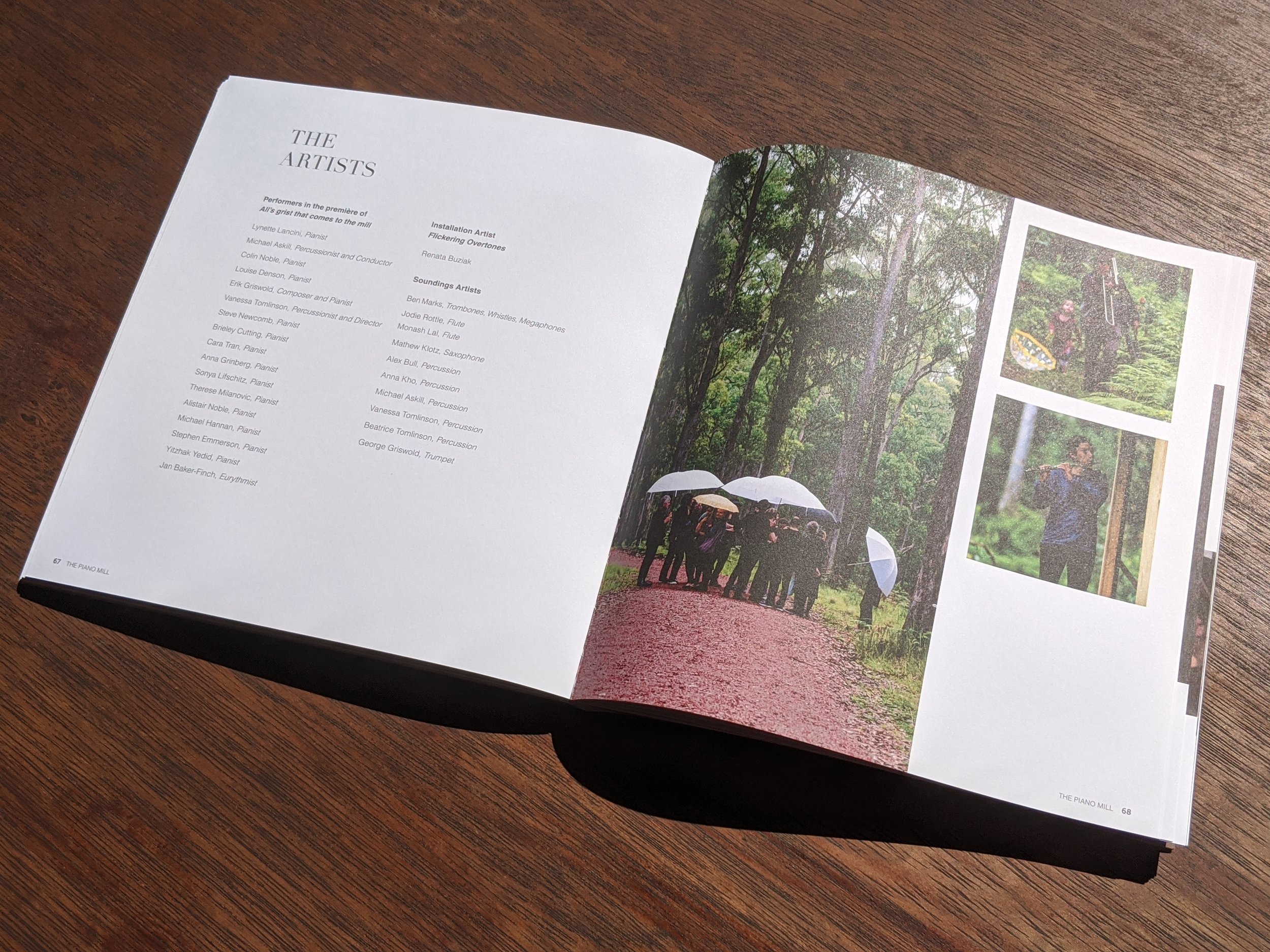

Over Easter 2016, 16 pianists from the local area and interstate, directed by Vanessa Tomlinson, were invited to help bring to life this one-of-a-kind, living slice of Australian musical history.

We’ve received so much love for the Piano Mill since its launch in 2016. Read some of the reviews below.

Find out more

Galleries

Videos

View past Easter events at the Piano Mill

Research

Jocelyn Wolfe

Pioneers, parlours and pianos: Making music, building a state in the Queensland bush.

The parlour was once the cultural heart and soul of the colonial home, a place for families and their guests to gather, entertain and socialise, as well as a place to retreat in private solace. More so, it was a woman's realm: what historian Therese Radic calls “a place of preserved memories, pianos, afternoon tea, tedium, respectability, and the vicar.”1 A woman tuned and practised the social mores of her family in this room, in that authoritative presence of a piano—lending its power and also its charm to her act.

Pianos and parlours have had a long association in Britain. Even in the antipodes, where the two are relatively recent arrivals on the landscape, they share a common heritage. We know that the first piano arrived with the first fleet in 1788, on the ship Sirius. It belonged to the surgeon, George Wogan. Jon Rose reports that by the end of the nineteenth century, the import of pianos had grown “from a nervous trickle to a barely controllable flood,”2 albeit overlooking the fine instruments that were already being made at home. Based on credible statistics, Rose suggests that as many as three out of four Australians may have owned a piano by the end of the nineteenth century. But how did the parlours, pianos and their players, exiles and emigrants of Britain and Europe, translate to the Queensland bush?

The arrival of free settlers, when the town of Brisbane became a municipality in 1859, also saw the arrival of the piano in the north; and as towns spread further northwards and westwards over hill and dale, their iron frames weighed heavily on the bullocks’ drays or camels’ backs. An eerie reminder of the piano’s early presence in regional Queensland is the “Piano in the tree” in Capricorn Street, Clermont. It is also a reminder of the height and ravaging force of the flood waters that ripped through the town in 1916. Although the piano is a replica today, the Issac Regional Council reports that there were originally three pianos found in trees after the 1916 flood. Clermont itself may provide the original ‘key’ to journeys of pianos and their destinations in the Queensland bush. Established in 1862, the town was the first inland settlement in the tropics and is one of the most historic town centres in Northern Australia.

With floods a feature of our new century, 100 years from the “Piano in the tree,” it’s timely to re-imagine the extraordinary music-making that happened in the most extraordinary places, well outside the formal surrounds of Brisbane society. Digging into archives and family albums, we see photos of handsome parlours—the family’s face to the world—in early Queensland homesteads, with ladies holding court at a piano. Yellowing keys, weathering timbers, and unmelodious tones aside, the piano and its home, the parlour, were a woman’s sentimental attachment to a world left behind, and a haven from the grind of living every day in the bush.

The stories of Queensland’s many musical lives nurtured in this way are yet to be told—fascinating stories about women, men and music-making in remote places, in punctilious parlours. What undiscovered imprints are left by those remote music-makers on the growing sense of identity and place in a state bristling with emigrants brandishing weapons against its native inhabitants and bustling with gold fever?

1 Radic, T. (2002). The lost chord of Australian culture: Researching Australian music history. In J. Southcott, & R. Smith (Eds.), Community of Researchers: Proceedings of the XXIInd Annual Conference (pp. 6-14). Melbourne: Australian Association for Research in Music Education.

2 Rose, J. (2008). Listening to history: Some proposals for reclaiming the practice of live music. Leonardo Music Journal, 18, 9-16. MIT Press.

Performance

Vanessa Tomlinson

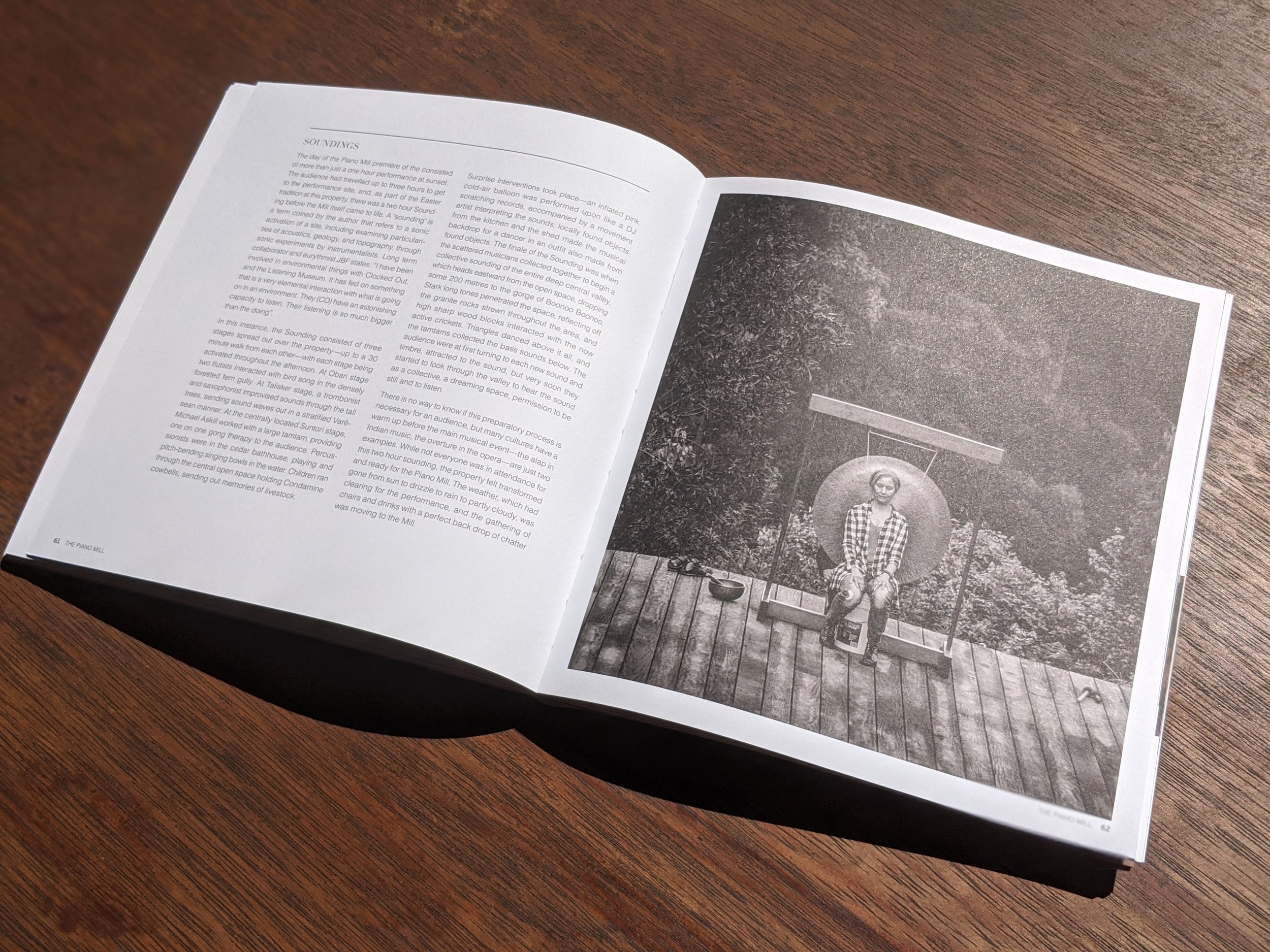

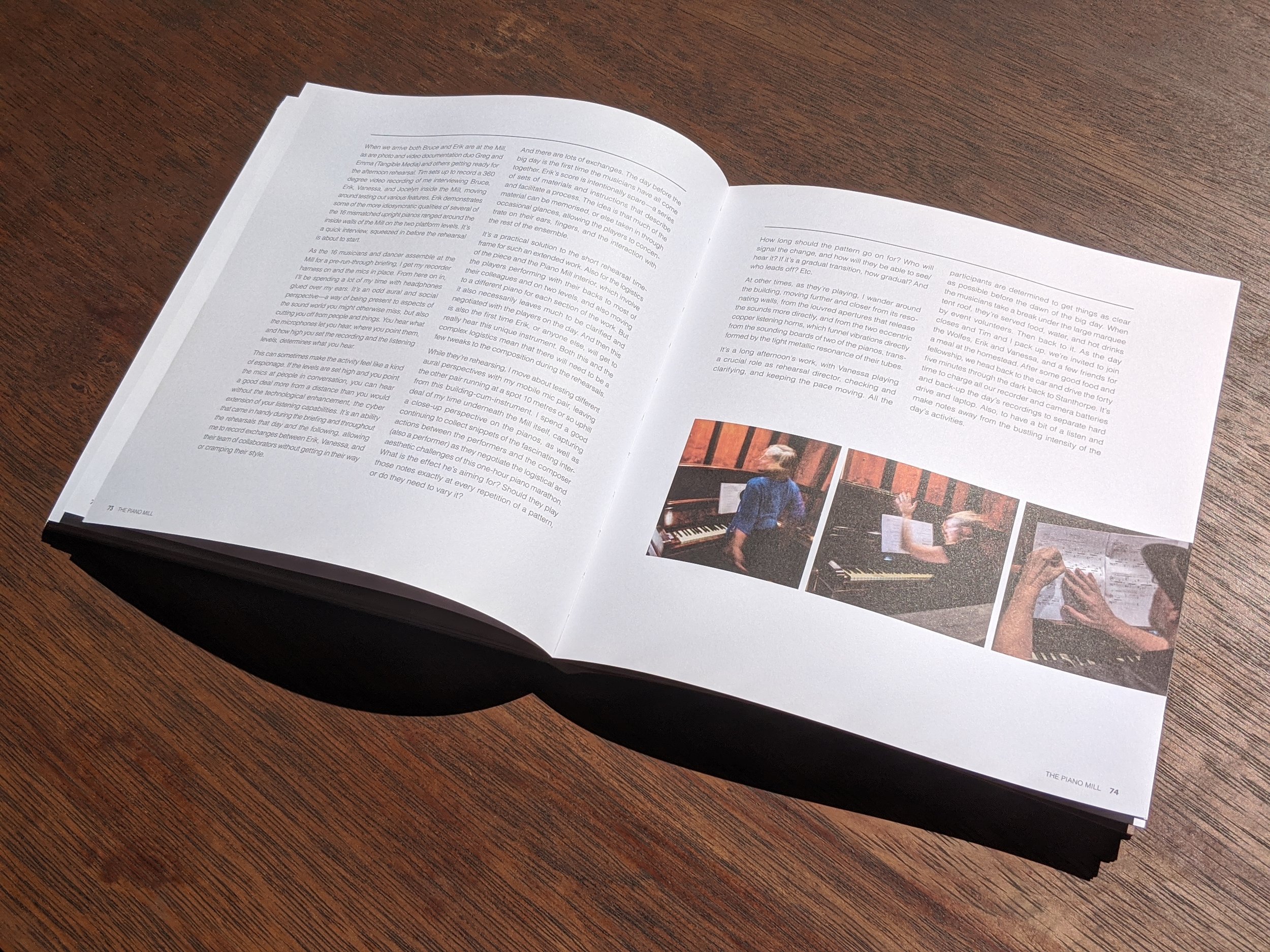

Music performance is a complex ritual of people, place, space and sound, whether in a concert hall or a pub. The Piano Mill explores every aspect of this complexity in a totally new arena for approaching the performance of a new piece of music; a site-specific performance venue, off the grid, in the bush, using reclaimed pianos set up in an unorthodox fashion. The event brings into contact 16 piano players to work together – already an unusual gathering – alongside an architect, builders, a chef, volunteers, a composer, a dancer, directors, film crews, recording engineers and a community of listeners. The work is subject to weather, power, natural sounds and extreme goodwill amongst the newly acquainted participants in the mill.

Architecture

Bruce Wolfe

I have known Jocelyn most of my life and Erik and Vanessa for more than a decade. Between them they have coloured what I think of as music and have certainly expanded my boundaries of appreciation when it comes to the experimental. Both as Clocked Out and as individuals they richly deserve reputations for innovation, and Jocelyn has coaxed me into an exploration and then a sheer delight in following their ever more adventurous exploits.

That would certainly explain some of the background to this current project.

My Architectural thesis in 1975 was titled “Some Societal and Historic Influences affecting the Australian Environment and the Architect’s Response”. One particular read was Australian History 1788 to 1888 in which I recall noting that during a significant part of that 100 year period, Australia possessed more pianos per head of population than any other country. I remember being more than a little amazed by that statistic but thinking on how the population was distributed it made a lot of sense.

Every homestead was a centre of entertainment, every town had a number of pubs and in each case, the piano was that vehicle for entertainment.

That notion obviously lodged fairly securely in my memory.

Move forward 35 years and Jocelyn, with her own interest in music, pianos and musical experimentation introduces me to the music and adventures of Clocked Out and to Erik Griswold who actually composes for prepared piano. It takes a while to really come to terms with owners of highly expensive instruments allowing Erik to tinker away inside their pianos to change their tonal qualities and actually accentuate their nature as a percussive instrument. And that he is quite famous for this is another revelation.

At some stage I obviously linked the two ideas and thought of all those pianos in rural Australia and elsewhere, quietly pre-preparing themselves to be written for by Erik.

So I guess this is why the collection of pianos, the story behind the number of pianos in the out-back, decentralization, pubs galore and every home becoming a centre for music- the parlour and its piano; Age and disuse preparing them for a new life.

The metaphor for this venture obviously had to carry the notion of their being many pianos so I thought of a collection of pianos. Not so much as one off instruments but as forming a complex instrument in its own right. So it was that I started to draw up arrangements for a piano room. I also needed to consult with the composer to see if he was willing to write a piece for what has come to my mind as a building powered by sixteen pianos.

The idea was to have these pianos packed fairly densely into a space and the design result is something of a cube; a floor plate of about 4.5 meters square allows 2 standard size upright pianos against each external wall. Two stories height produces sixteen pianos. Raise the cube off the ground to allow the pianos to be moved in and raised up through a hole in the middle of the floor and place a clearstory at the top and we have the basic shape.

Large vents on the side allow the sound to be modulated and these could be operated with large levers on the outside which could add more theatrics to the performance. The arrival of the musicians too would be quite theatrical as they bow to enter under the building and start their ascension to the two levels of pianos. Translucent slots on the sides of the cube would allow some visibility of the musicians to an outside audience.

It was not surprising to me that Erik was immediately on board and so it then became an issue for me to continue the design and of course find the pianos.

It is simply amazing how many people have pianos that are not in use. It does give further validity to that notion of a land over-run with old pianos. Most come with an interesting story and there are also many stories about picking them up, hiring trucks, unloading with a tractor and uncomfortable trips to Stanthorpe in an old Ute with two pianos on the back making for a fairly slow trip as well. There are pretty interesting scenes of a garage full of pianos at home in Paddington and an even more crowded shed at Harrigans Lane as the pianos multiply.

The design has also progressed to be ready to start construction. Copper clad to allow the building to age as gracefully as the pianos, a very stiff frame of Ironbark with seasoned ply to provide a resonant diaphragm and bronze toned acrylic slots to give the obscure view in and the warm glow internally. But every part of the construction too has a story. The 7m long ironbark corner posts had the saw-miller searching for trees straight enough to cut these 175mm square posts and extending a kiln to dry them in.

We were pretty catholic in our piano collecting and one or two of the pianos may be a little too pre-prepared so the search for more pianos continues. There was also the request from the ever willing composer for pianos to be placed in the bush while he was seeking inspiration. One of these was taken by tractor, high up on the forks at the front of the tractor trundling down a bush track, to what was at one stage optimistically called the boat shed. It is a shelter beside the property’s main dam. It was rechristened the gin and tonic platform when the water in the dam went down. With the arrival of the piano it has been renamed The Piano Bar and with the renaming the water level in the dam returned.

So the project commencing as a series of vague ideas a couple of years ago is now well underway and we have a target date for the performance of the piece for this peculiar instrument. At Easter 2016 it will be the 10th anniversary of our acquiring the property at Harrigans Lane and 10 years since we started to promote the idea of using the property for arts events and encouraging artists to use the land and buildings as facilitators for innovative arts.

The relatively early commencement of the building and the collecting of the pianos at this time should allow the composer reasonable time to get to know his instrument as it will be an amazing feat to write for what are very individual and eccentric components. It will also allow time to refine the performance of the building and its acoustics.

For me it will be a time to work on the other ideas that inhabit the instrument, a collection of tuned grader blades that can be struck as chimes or played with a bow. Bass strings suspending the heavy grader blades another opportunity and there are other notions that may or may not be utilized by Eric for this piece for sixteen pianos.

We liked the notion of just calling this building the piano room: understated and then also surprising when the idea gets unpacked; but as a fairly common expression, there was no way it would stand as a domain name so other names have been proffered. Hyper-cube, Piano Fort, piano cubed etc. but we have settled on the Piano Mill, Jocelyn’s idea:

A mill conjures up a tall building made of lovely raw materials like stone, brick, timber, and even raw metals like copper. It’s full of machinery that clanks, clinks, bangs, beats, strikes, hammers, and grinds, and transforms things—changes things from something raw to something refined: timber to paper, grain to flour, coffee beans to grounds, iron ore to steel.

What if the machinery were pianos, and the grain were pitches, and all the pitches, beaten, struck, and ground were turned into music?

The pianos sit, stacked, waiting to be assigned their milling tasks. The miller arrives. Yes, the missing piece: How can machinery operate without a driver, or a brain?

The adventure begins!

Composition

Erik Griswold

I first met Bruce and Jocelyn Wolfe in 2007, when they took a chance and commissioned my composition “A Wolfe in the Mangroves” (originally “Concerto for Prepared Piano and Percussion”). Their support meant a lot to me and it inspired me to create something special - “A Wolfe” is one of my most played compositions to date. In the years since, Bruce and Jocelyn have become integral members of the Clocked Out family, traveling from outback Queensland to Stradbroke Island to Southwestern China to experience and take part in many of Vanessa Tomlinson and my creative projects.

Since Bruce bought his bush property at Harrigan’s Lane, near Stanthorpe, I’ve watched his own creativity flourish through his imaginative architectural designs. The property has become a focal point for artistic exploration, and his own creative projects have expanded into new directions. At the same time he’s taken an increasingly active role in his support and encouragement of artists, musicians and performers, hosting mutli-media performance events and artist residencies. The Piano Mill represents the ultimate expression of Bruce’s creative vision, a radical concept that is at once an intriguing architectural structure, a musical instrument, and playful invitation to collaborate. And I’m super excited to be on the receiving end of this invitation!

As a composer, The Piano Mill presents an unprecedented musical opportunity, and although I am very reluctant to make the claim that “it’s never been done before,” I think it’s fair to say the project has some unique features!

First, the pianos:

There are sixteen of them! Though there have been other multiple piano events (I have heard of two or three in recent memory), there is no extensive repertoire for sixteen pianos I can consult to find out how it’s done. And while I’ve written for one and two pianos before, it’s difficult to envision (or “auralize”) the sound of 16 pianos. Bruce has set the general principal that the pianos are played “as is.” These are old pianos with a bit of wear & tear. Some with a lot of wear & tear. Each piano has it’s own idiosynchrasies - some are out of tune, some have bung notes, broken action, or corroded strings. Creating a coherent musical sound out of all these quirky and individual instruments will be a challenge.

Second, the architecture:

Bruce’s architecture has some really interesting implications for the music. Aspects of the architecture suggest things about the musical stucture, spatialization, and tone.

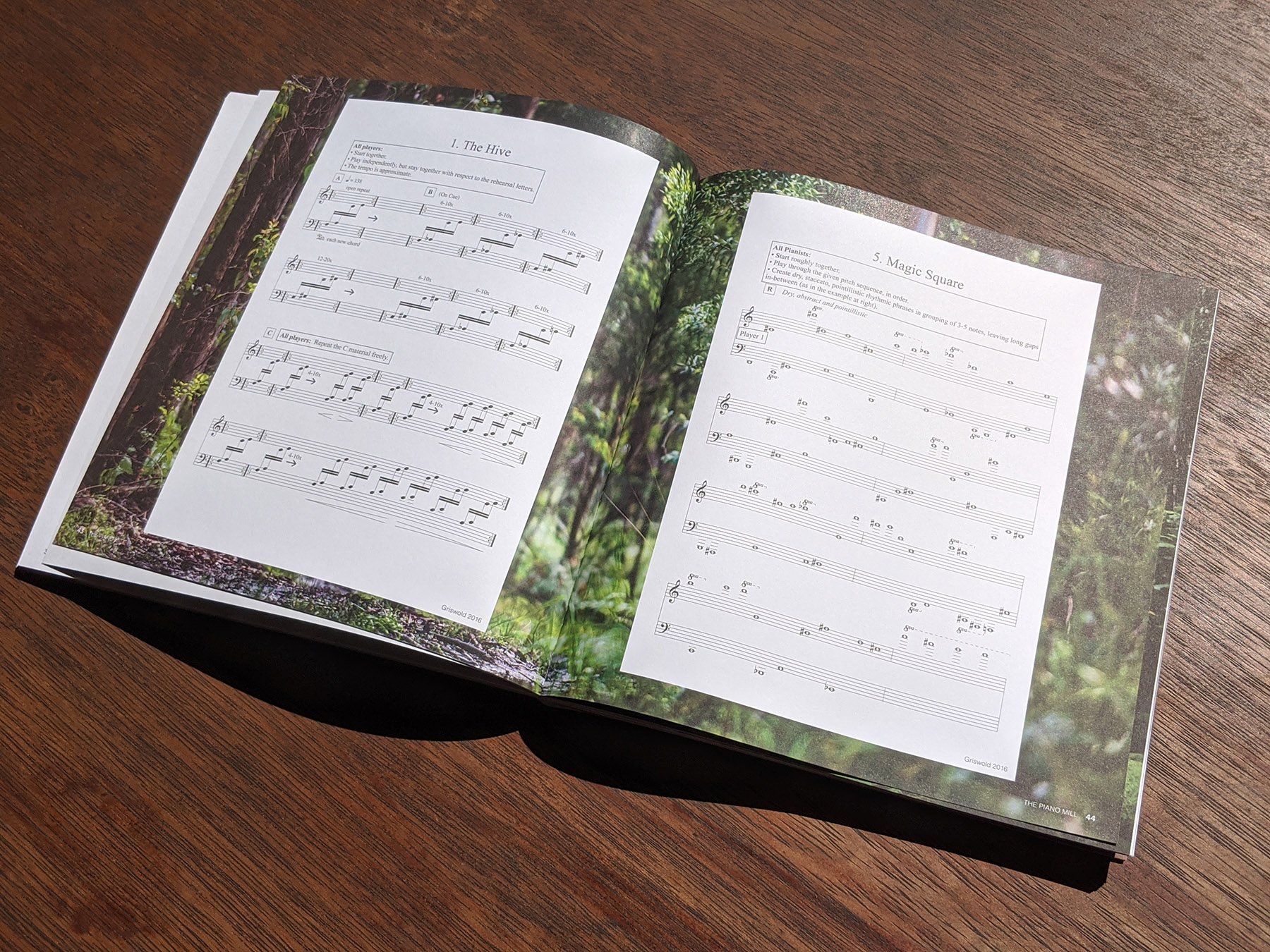

The building is specifically designed around the dimensions of the piano. There are two levels in the building, each containing eight pianos, with each wall holds two pianos side-by side. Bruce and I have discussed the idea of the two levels having a different sound. The concept is that the upper level would contain relatively in-tune, good quality pianos, while the bottom level would contain wonky, out-of-tune, prepared sounding pianos. The symmetry of the design, with upper and lower levels, four pianos per side, has some interesting structural implications for the music. The idea of antiphonal or spatialized, hocketing rhythms could bring out the qualities of the architecture – the sound could move from top to bottom, left to right, in circles or back and forth. In a great acoustical innovation, Bruce has fashioned eight louvers, or “sound vents” into the building, which can be manipulated during the performance to affect changes in dynamic and tone quality. He envisions that one to four operators would manually open and close the louvers at different points to create softer and muffled, or louder and bright effects. I also think they could also create an enhanced directionality in the music.

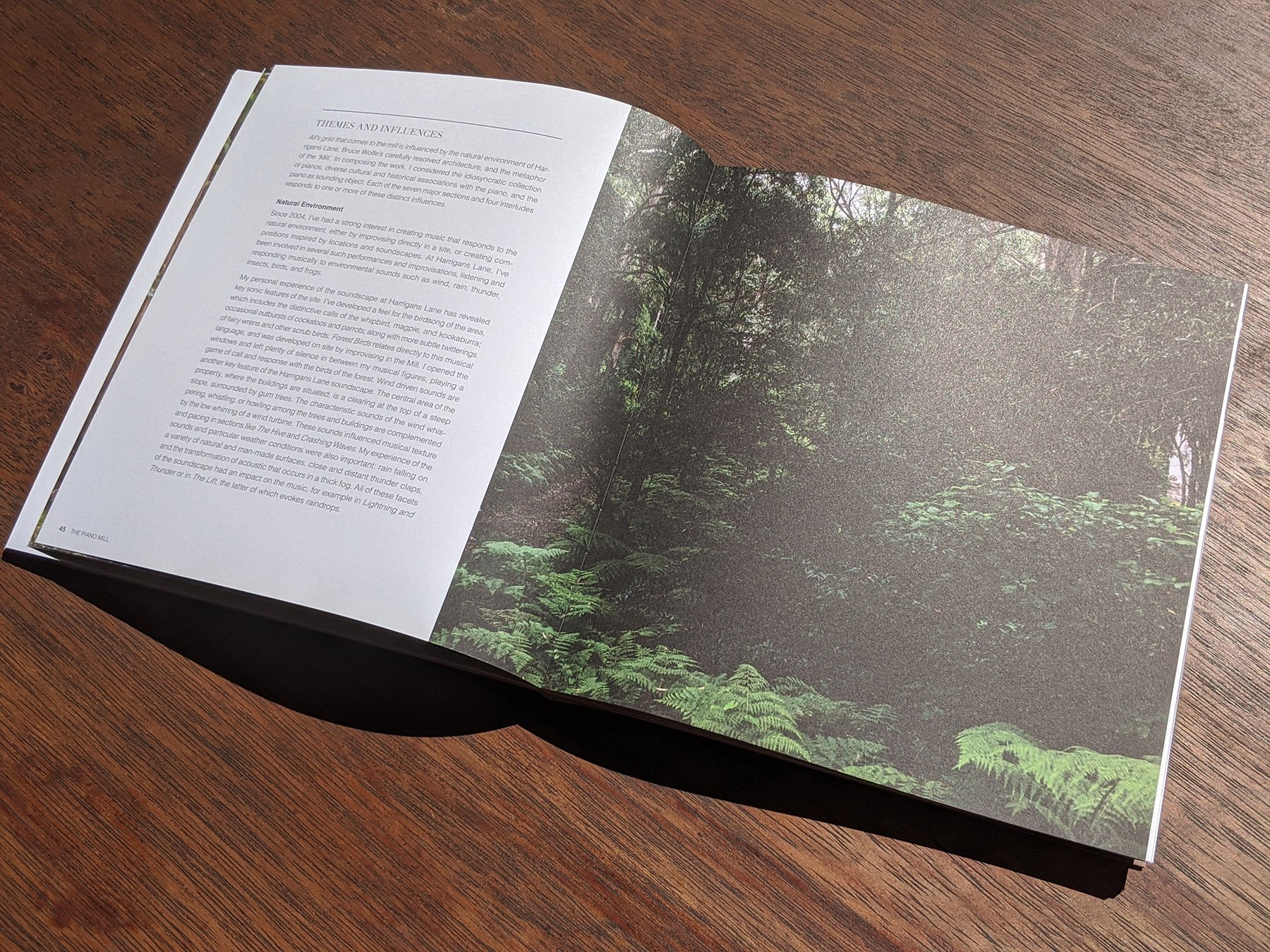

Third, the environment:

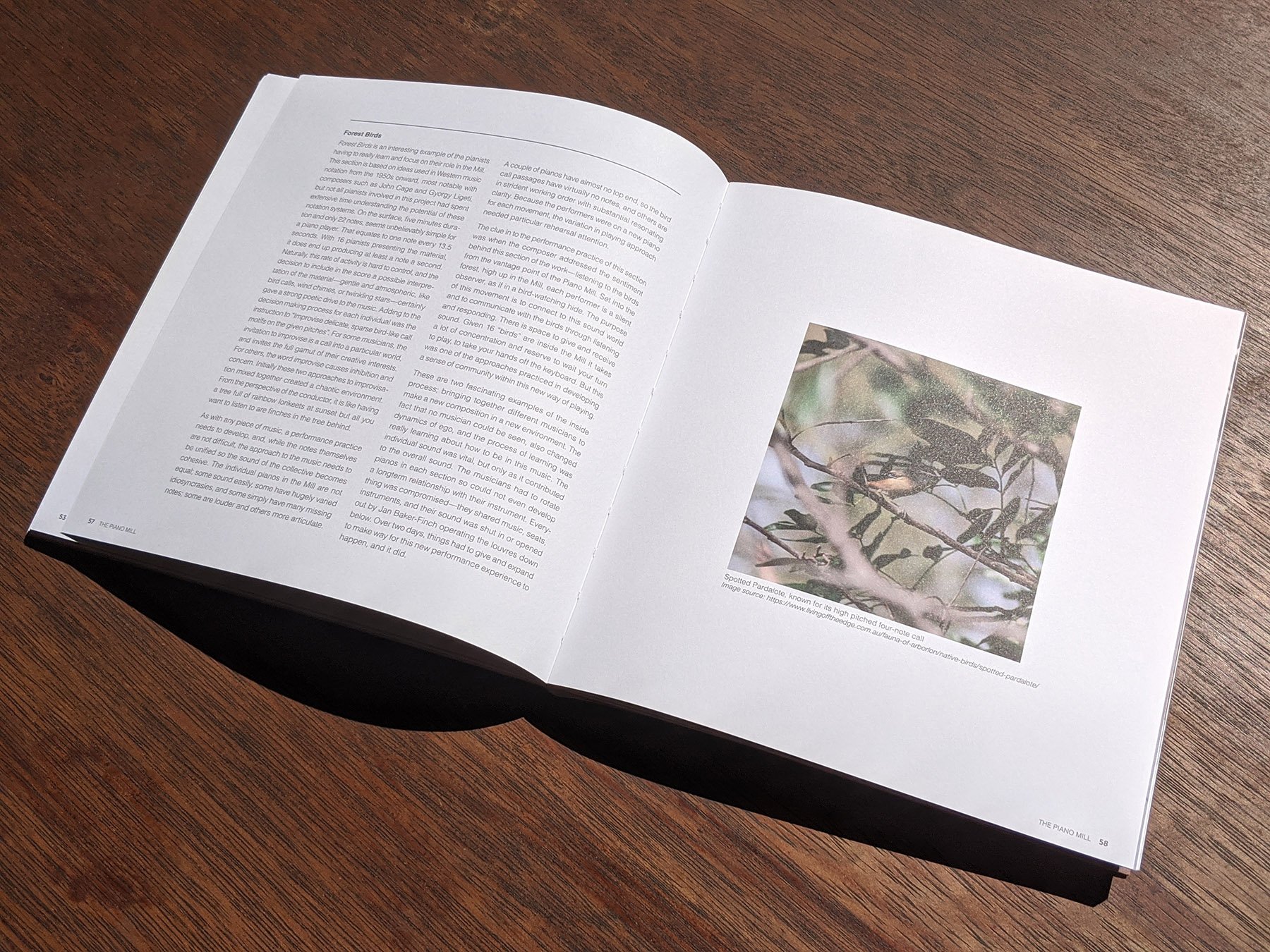

Since 2004 I’ve had a strong interest in the idea of “environmental music.” This means creating music (improvised or composed) that responds to a natural environment. In some cases I’ve improvised directly in a particular environment, listening carefully to the ambient sounds, and entering into a music dialog with them. In other cases, I’ve spent time experiencing and listening to a particular environment, and then created a composition based on the natural sounds, which might be played in a concert hall or other venue. At Harrigan’s Lane, I’ve been involved in several such performances and improvisations, listening and responding musically to environmental sounds such as wind, insects, birds, and frogs. I hope to also reflect the sounds of the local environment in The Piano Mill.

Bringing together all these elements in one piece will be challenging, to say the least, but in a good way. Can’t wait to put all this together in 2016!

Banner images by Tangible Media, Richard Brimer, and Marc Treble.